| 作品 Works |

| 评论文章 Article |

| 随笔及访谈 Essay and Interview |

| 个人简历 Biography |

| 联系方式 Contact |

Yang Jinsong: the Life of a Young Painter in Beijing |

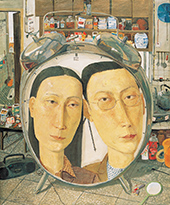

Yang Jinsong is living at high speed. The young artist commutes to the Academy of Fine Arts in Chongqing where he was educated and is now employed as an art instructor; to Beijing's Xili District where he and his wife currently live; and to his new studio near Beijing Airport, a complex of brick warehouses recently constructed for artists. In a frenetic contemporary art scene in which young art school graduates compete in producing sensational art to attract the attention of curators and western collectors, Jinsong's paintings stand out as highly intimate and personal views of his world. Not shocking or garishly colored, not oversized or cast in some dramatic installation mode, his paintings detail the everyday objects that fill his life. If the adage is true that you can judge one's character by the friends he keeps, then looking at the exact and vibrant depiction of Jinsong's world will give you the impression of knowing him, intimately. Trained at the Chongqing Academy of Fine Arts, Jinsong was a consummate master of figure painting, displaying all the academic skills that accompany Western art. This is evident in one of the early paintings he made in 1999, a self-portrait with his newly married wife. Chinese art schools have been quite successful in turning out artists of accomplished skill in the field of representational painting, though ironically, Western schools no longer focus on classical technique. Indeed the current generation of Chinese artists bemoans the outdated curriculum, and like everything else in China, changes are being made at breakneck speed. In the past few years, installation and video art have come to account for 80 percent of China's total artistic output. Though Jinsong rejects the suave classical technique he mastered in the academy, he affirms that painting requires artistry. To be brilliant at the age of 20 is nearly impossible because building technique and skill takes time. Forgetting his training, he transformed his paintings into childlike images of everyday objects, painted observantly and naively. Such a transition in his work is related to the physical and mental difficulties he experienced as a young man, just after college. Like many other art students, Jinsong was focused on success and to that end he painted so much that he ended up in a state of exhaustion, physically debilitated and hospitalized. Unable to tolerate confinement in the hospital, he remained at home, returning for check-ups with his doctor, who marked his progress and continued to warn him not to work or at least to limit his work-time, for he needed rest. Unable to give up art, Jinsong limited himself to small dark-pencil drawings. The illness─a combination of anxiety, high fever, and hormonal imbalance─lasted two years. When Jinsong met his wife, he had already largely recovered and had tentatively resumed painting. One of his first works was a portrait of them together, a theme he would continue to pursue for more than five years. Long-limbed, graceful and beautiful, his wife Shecai appears as his twin. At first she is independent, as in a painting from June 1998. Their heads and upper bodies are inscribed within the roundel of the face of an old-fashioned alarm clock. Placed on a kitchen counter in the foreground, the clock is oversized in the close and intimate apartment. Jinsong painstakingly delineates the multitude of everyday objects that fill up the cramped apartment. In the organization of the interior space and the meticulous drawing of the furniture and household articles in Western perspective, and in line with the orthogonals of the picture, Jinsong creates a magical illusionism that resembles the work of the Netherlandish Renaissance painters such as Roger Weyden. The painting is also a celebration of the manifestation of the spiritual in the material. The objects take on an iconic status, subject to the two large-scale figures for their meaning and use. Jinsong, like the Dutch painter, directs the eye around the room by careful placement and perspective-drawing of the household objects: to the far left and in the background is a deeply-recessed, small bathroom, with tiled floor, soiled walls, a mop in a bucket, and a light-filled window. This is an honest record of the less-than-ideal circumstances of his living space. Occupying the upper center are wooden shelves filled with bottles and half-used products and to the right is the stovetop with tea kettle, cooking implements, and an electric fan. The outline around the still, white central space of the huge clock is drawn with centripetal force, and the light reflecting off its twin aluminum bells is illusionistically realized. Within the orb the figures are carefully delineated, revealing their innermost character: Shecai, reserved and meditative, inclines her head, gently touching his with an expression of eternal patience; Jinsong, leaning his head towards hers, looks out at the viewer somewhat warily, his right eye directly confronting the viewer, the left turned slightly inwards in contemplative mode. A sense of silent communication informs their closed-mouth, elongated faces. A somber mood pervades the palette: the clock, walls, and floors are a muted grayish-white, and the kitchen cabinets are dark brown. But the tiny objects in the apartment, colorfully painted according to their actual appearance, create pulses of bright color in various shapes, causing a staccato rhythm to beat against the stillness of the clock. Like a mandala, small narrative details carefully placed along the perimeters draw one to the calm center and to the frenetic activity their presence implies, momentarily quelled by the union of the couple. By 2001 the loving couple no longer inhabits an independent space: like Siamese twins, they share the same body in Daily News. Much of the style of the 1998 portraits is similar. The calm center is dominated by a neutral grayish-white, while the deep perspective, here, is out of a window: the neighborhood's low-rise buildings and streets still empty of early morning traffic; beyond the green hills along the banks of a river punctuated with an industrial bridge, factories, and stacks along its shore, a large steamer navigates the waters. In the kitchen everything is in motion: the doors of the cabinets and appliances are open, an open faucet drips on the dishes in the sink; everything is being used. The hundreds of small-scale objects in the kitchen are scrupulously rendered: cooked food waits in pots and pans, used kitchen utensils…open jars of spices and sauces. Life is moving at its harried pace, breakfast is made, it's time to start the day. But the couple momentarily stop, sharing a headset to silently listen to music. Unaware of the viewer, her expression placid and demure, Shecai looks to the left and inclines toward Jinsong. Jinsong looks directly to the viewer, less wary than before, perhaps even proud of his life, animated by his wife's activities. A garbage pail in the right corner overflows with refuse. In the mundane representation of his daily life, Jinsong finds himself. But ruefully, he explains, his generation is quite different from the preceding one that lived through the Cultural Revolution. They had an agenda, something to struggle against, something larger than themselves that informed their work. Making art after the turmoil seems problematic. Can you justify painting your kitchen appliances? He adds that Anti-Cultural Revolution art and political Pop, both using portraits of Mao and such, easily fit into the Western agenda. Collectors and curators come to China ready to appreciate such work but look askance at art that is less politically-motivated. Beginning in 2000, Jinsong changed the composition again. Now out of the apartment, the couple occupies the natural world. In one painting they seem to emerge from a cabbage patch of super-sized vegetables. The heads, now conjoined and bearing solemn expressions, sit upon a hermaphroditic naked body. The trash of civilization drifts about: a TV screen displaying the Forbidden City, a computer mouse, electric outlets filled with plugs, music speakers, telephones, a laptop computer, lipstick, perfume, cigarette butts, candy wrappers, paper receipts, and other consumer articles infect the terrain like parasitic insects. Now outside of their home they have lost their mythic scale, and the outside world is crowding them; and yet, undeniably, they are more intimately related to each other and to the natural world out of which they surface. The series of works from 2002 includes a large watermelon or long squash out of which a section has been cut, leaving small interior views of the couple. Still sharing a body, the two impassively look out from a gourd which hangs from a delicate vine; at top is a computer on a desk, to the right is the Forbidden City, to the left a great dam and a block of apartments; a TV seems plugged into the gourd. In addition to the obvious anti-consumerism stance, Jinsong's work is a paean to marital love. He talks hauntingly of his parents who he describes as old fashioned, how his father has been nursing his mother for over twelve years and how that sense of loyalty and devotion is now quaint. Jinsong clearly transmit these values in his portraits. By 2003 the cat appears. A cat is noticeable in the early works…walking through an interior, seated on its haunches. But in the 2003 series the cat is huge; it is, Jinsong admits, a self-portrait. Sometimes the cat is lazy and free from strife, rolling on its back and waiting to be stroked; sometimes it is sleeping on its side, among scattered watermelon rinds; at other times its bloodshot eyes are frenzied. These paintings often look unfinished. The images only partly cover the canvas, the cat sketchily painted with light feathery strokes of pigment, its fur standing on edge. Around the centrally-seated cat are pencil sketches of a helicopter on the right, of jet planes releasing bombs and coca-cola bottles in the upper left, and below, near the cat's paw is a delicately drawn image of a Confucian scholar. Toy planes and a whistling kettle surround the cat. In another, the cat strides out stepping over the consumables enumerated above, the sketchily drawn object in the upper-left background is a factory's twin smokestacks spewing fumes. Jinsong's most recent paintings are getting larger, no doubt as a result of his bigger studio space. Also some of the tension seems to have abated. As in his prior works, the concern with scale relationships continues but now the disparity in the size of the objects is surrealistic: a large glass is filled with tea leaves, among which the joined-head portrait appears; at the bottom is a miniscule construction site with an earth digger; floating in the liquid are cash receipts, a skinned chicken, and a helicopter. A freighter with steaming smokestack sails on top of the sea of tea, and hanging off the rim of the glass is a minute red sock. Suggesting the perspective of a small child in a grown-up world, other works display an oversized cigarette tray, a bowl of soup, or a bathroom sink in which small-scale, freely drawn objects from everyday life are painted in bright colors. But the tiny toy-like details are witty plays on the relativity of size: the kitchen sink, filled with water dripping from its faucet, is home to an island: at its crest is a miniscule portrait of the artist and his wife. Spent cigarettes, airplanes, and watermelon rinds float in the surrounding sea; an electric plug immersed in the water dangles off the side of the sink; and near the faucet, toothpaste oozes out of its tube. Another painting, this time of a giant ashtray filled with butts, is home to an assortment of tiny, used consumer objects; the artist and his wife peer out among the ashes at a construction site under development and electronic debris: TV sets, a telephone wedged in among the butts. These large paintings of oversized objects elicit Lilliputian images of a gargantuan race, or the worlds within worlds found under a microscopic lens. As in a child's dream, one is threatened by oversized elements that are impossible to control, destructive agents that pollute the environment, rampant consumerism, construction projects that level the old city of Beijing with new shopping malls and high-rise apartment buildings, and sometimes the hint of war. In this evocation of the artist's life in Beijing, he draws a portrait of the problems of our contemporary lives. So too the threat of militarism, consumerism and pollution is clearly drawn in the details of these paintings. There are more hopeful aspects too. The couple is still together, still united, and as a landscape of the most recent period suggests, there may be a peaceful resolution, a Taoist escape to the hills: emerging from the clouds, the couple nests on a mountain top, while hints of the real world are still perceptible, like the helicopter, derricks, and factories. Looking at Jinsong's imagery brings to mind an early 70s Joni Mitchell lyric, "They paved paradise and put up a parking lot." Yang Jinsong was born in Chongqing, China, in 1971. He has had solo exhibitions in Germany in 2004, and in 2000 at Schloss Schenfeld in Kassel, Germany, Galerie Stellwerk (Kassel) and Art Now Gallery in Beijing. He has participated in group shows in Singapore, Rome, Toulouse, Budapest, and elsewhere.

|